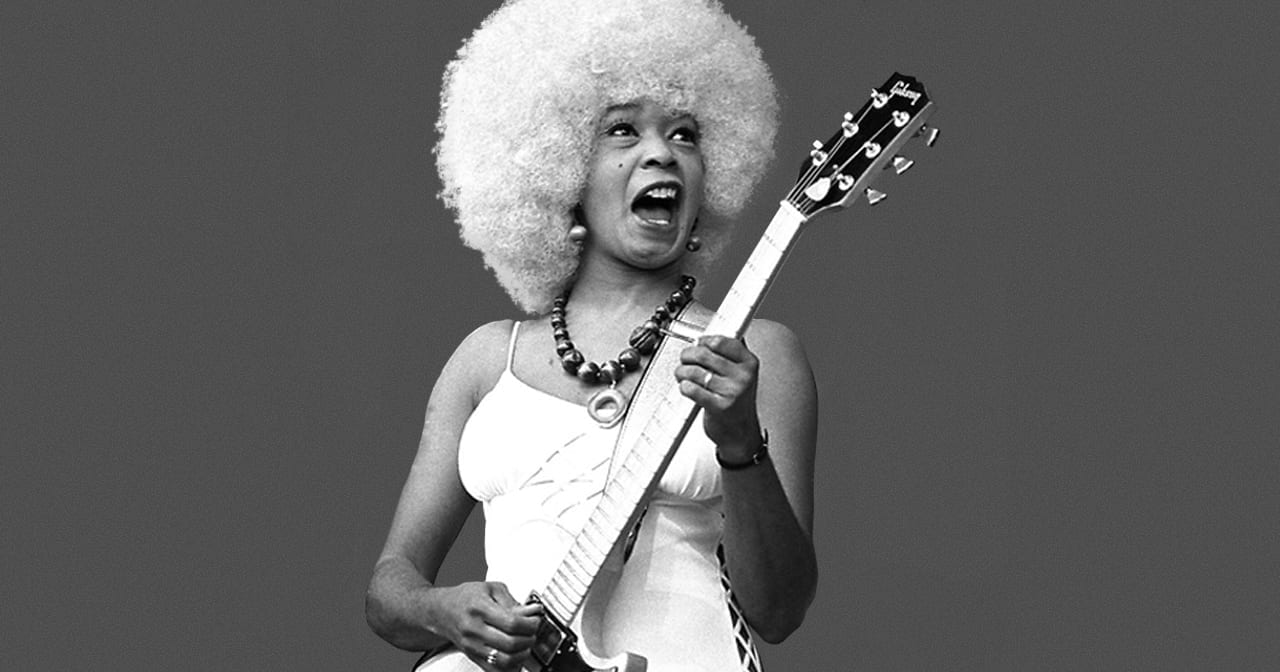

Born in 1949 in Burbank to a show biz family, Bonnie Raitt plays the slide guitar like she was born in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Her first exposure to the music scene was classical piano (her mother’s forte), her father’s Broadway show tunes, and the Beach Boy harmonies she grew up with. A Christmas gift changed Bonnie’s life—at age eight, she received a guitar and worked diligently at getting good at playing it. The first time she heard Joan Baez, Bonnie went the way of folk and moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to be a part of the folkie coffeehouse scene. Unfortunately for her, folk music was on its last legs. Instead she hooked up with Dick Waterman, a beau who just happened to manage the careers of Bonnie’s musical icons: Son House, Fred McDowell, Sippie Wallace, and Muddy Waters. By the age of twenty, she was playing with Buddy Guy and Junior Wells—opening for the Rolling Stones with two blue greats.

Bonnie’s road to fame, however, was very long and winding. It had to come on her terms. Always more interested in artistic integrity than commercial

success, she had exacting standards and tastes. She demanded authenticity in playing the blues she loved and reinterpreting those riffs through the influences of country and rock. She didn’t play the game and, a musician’s musician, she rarely got radio air play. Thus she made her living traveling the country, performing in small clubs. Bonnie was also very outspoken on political causes. Raised as a Quaker, she has always been involved in political causes, doing many benefit concerts; in 1979, she cofounded Musicians United for Safe Energy.

The stress of the road, and of being a novelty in the music industry—a female blues guitarist—eventually took its toll, and Bonnie drowned her sorrows for a time in drugs and booze. In the mid-eighties, when her record label dumped her, she bottomed out, became clean and sober, and made the climb back up. In 1989, her smash album “Nick of Time” won her a Grammy and garnered sales in excess of four million.

Since then, she hasn’t stopped making her great earthy blend of blues, folk, pop, and R&B, or working on behalf of the causes that are meaningful to her. Bonnie Raitt is a consummate musician who loves to perform live, loves to pay homage to the blues greats, and continues to speak her mind. In an interview in Rolling Stone, she laid it on the line about the current looks-dominated music industry: “In the 70s, all these earthy women were getting record deals—you didn’t have to be some gorgeous babe. There’s been some backsliding since.”

“Any guy who has a problem with feminists is signaling a shortage in his pants. If I had to be a woman before men and women were more equal, I would’ve shot somebody and been in jail.”

— Bonnie Raitt

This excerpt is from The Book of Awesome Women by Becca Anderson, which is available now through Amazon and Mango Media.