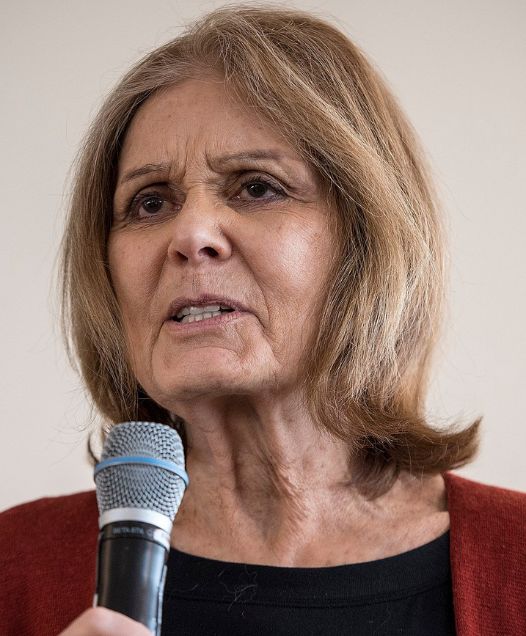

Gloria Steinem’s name is synonymous with feminism. As a leader of the second wave of feminism, she brought a new concern to the fore—the importance of self-esteem for women. Her childhood did little to bolster her sense of self or predict the successful course her life would take. Her father, an antique dealer, traveled a lot for work, and her mother suffered from severe depression and was often bedridden and self-destructive. Because they moved so often, Gloria didn’t attend school until she was ten, after her family was deserted by her father and Gloria assumed the roles of housewife and mother to her mother and sister. Escaping through books and movies, Gloria did well at school and eventually was accepted to Smith College, where her interest in women’s rights, sparked by her awareness that her mother’s illness had not been taken seriously because “her functioning was not necessary to the world” began to take hold.

After a junket in India, she started freelancing; her goal was to be a political reporter. Soon she hit the glass ceiling; while she made enough money to get by, she wasn’t getting the kind of serious assignments her male colleagues were—interviewing presidential candidates and writing on foreign policy. Instead she was assigned in 1963 to go undercover as a Playboy Bunny and write about it. She agreed, seeing it as an investigative journalism piece, a way to expose sexual harassment. However, after the story appeared, no editors would take her seriously; she was the girl who had worked as a Bunny.

But she kept pushing for political assignments and finally, in 1968, came on board the newly founded New York magazine as a contributing editor. When the magazine sent her to cover a radical feminist meeting, no one guessed the assignment would be transformational. After attending the meeting, she moved from the sidelines to stage center of the feminist movement, cofounding the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Women’s Action Alliance.

The next year, Steinem, with her background in journalism, was the impetus for the founding of Ms., the first mainstream feminist magazine in America’s history. The first issue, with shero Wonder Woman on the cover, sold out the entire first printing of 300,000 in an unprecedented eight days, and Ms. received an astonishing 20,000 letters soon after the magazine hit the newsstands, indicating it had really struck a chord with the women of America. Steinem’s personal essay, “Sisterhood,” spoke of her reluctance to join the movement at first because of “lack of esteem for women—black women, Chicana women, white women— and for myself.”

The self-described “itinerant speaker and feminist organizer” continued at the helm of Ms. for fifteen years, publishing articles such as the one that posited Marilyn Monroe as the embodiment of fifties women’s struggle to keep up the expectations of society. She penned Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions in 1983, urging women to take up the charge as progenitors of change. This was followed by Revolution from Within in 1992, illuminating her despair at having to take care of her emotionally disturbed mother as well as her struggles with self-image, feeling like “a plump brunette from Toledo, too tall and much too pudding-faced, with…a voice that felt constantly on the verge of revealing some unacceptable emotion.” Steinem stunned her reading public with such self-revelatory confessions. Who would have guessed that this crack editor and leading beauty of the feminist movement had zero self-image?

Gloria Steinem’s real genius lies in her ability to relate to other women, creating the bond of sisterhood with shared feelings, even in her heralded memoir. Still a phenomenally popular speaker and writer, Gloria Steinem crystallizes the seemingly complicated issues and challenges of her work by defining feminism as simply, “the belief that women are full human beings.”

“The sex and race caste systems are very intertwined and the revolutions have always come together, whether it was the suffragist and abolitionist movements or whether it’s the feminist and civil rights movements. They must come together because one can’t succeed without the other.”

— Gloria Steinem

This excerpt is from The Book of Awesome Women by Becca Anderson which is available now through Amazon and Mango Media