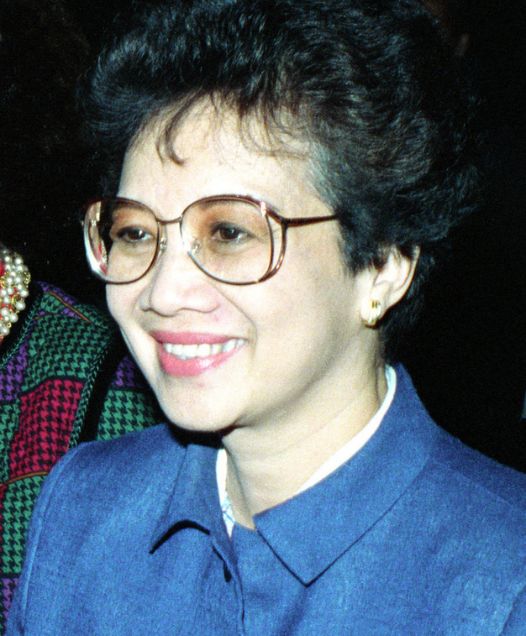

Hot on the heels of anti-shero Imelda Marcos (or should I saw hot on the 1,600 heels; remember the 800 pairs of shoe scandal?) came Corazon Aquino, a political neophyte who quietly and competently took the helm of the volatile islands nation in the aftermath of the Marcos regime.

Cory didn’t set out to run a country. Educated in the Catholic school system in the United States and the Philippines, she abandoned higher education to marry Benigno Aquino, a promising politician, and served as his helpmate and mother of their five children. Benigno opposed the martial law of Marcos and was jailed in 1972; when he was released, the family fled to the United States, where they lived until 1983. By this time Marcos was losing control of the reins of power, and Benigno decided to return to help agitate for his resignation.

As the Aquinos stepped off the plane, Benigno was assassinated. In that moment, Cory had to decide—turn tail or take up the mantle of her slain husband. She chose the latter, uniting the dissidents against Marcos. In 1986, she ran for the presidency of the Philippines, abandoning the speeches that had been prepared for her to talk of the suffering that Marcos had caused her in life. Although both sides declared victory, Marcos soon fled and Cory assumed power.

After the tabloid dictatorship style of the Marcos family, the widow-turned-stateswoman stunned the world with her no-nonsense manner and absolute fearlessness. Corazon Cojuangco Aquino stood fast amid the corrupt circus of Filipino politics even though coup after coup attempted to remove her from office. She quickly earned the respect of her enemies when they discovered it wasn’t so easy to knock the homemaker and mother of five from her post as president of the explosively unstable nation. And she refused to live in the opulent palace the Marcos had built, proclaiming it a symbol of oppression of the poor masses by the wealthy few, and chose to live in a modest residence nearby.

However, longterm leadership proved difficult. Although she was credited with drafting a new democratic constitution that was ratified by a landslide popular vote, her support dwindled in the face of chronic poverty, an overstrong military, and governmental corruption. Her presidency ended in 1992.

For her achievements and courage, Cory Aquino has received numerous honorary degrees from sources as diverse as Fordham University and Waseda University in Tokyo. Named Time magazine’s Woman of the Year, Cory is also the recipient of many awards and distinctions, including the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award, the United Nations Silver Medal, and the Canadian International Prize for Freedom. Acknowledged by the Women’s International Center for her “perseverance and dedication,” Corazon Aquino was honored as an International Leadership Living Legacy who “faced adversity with courage and directness.”

This excerpt is from The Book of Awesome Women by Becca Anderson which is available now through Amazon and Mango Media